For Bowie Fans - Collaborators Shaping the Sound: From Research to Art Print Music Map

by Mike Bell

·

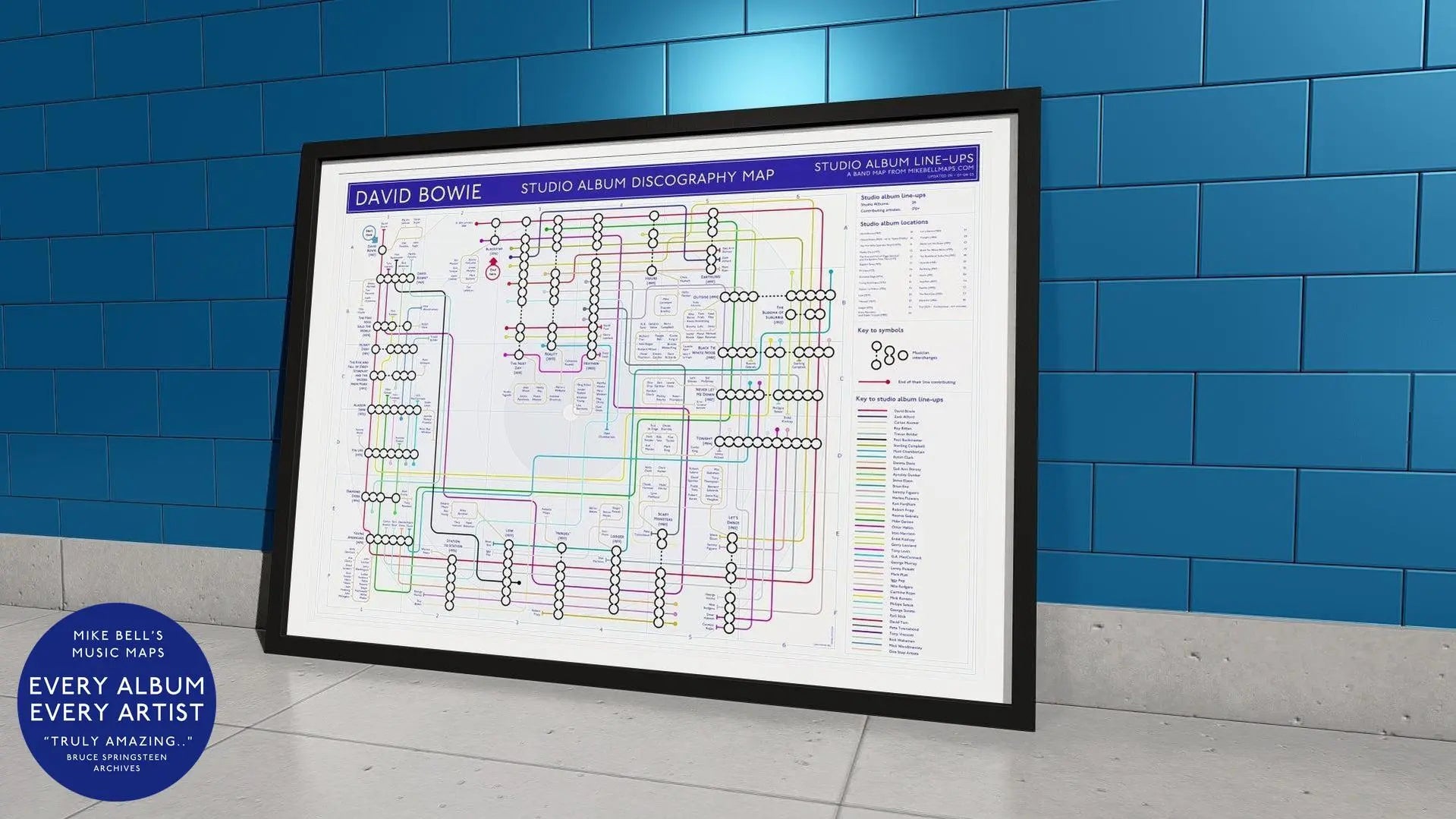

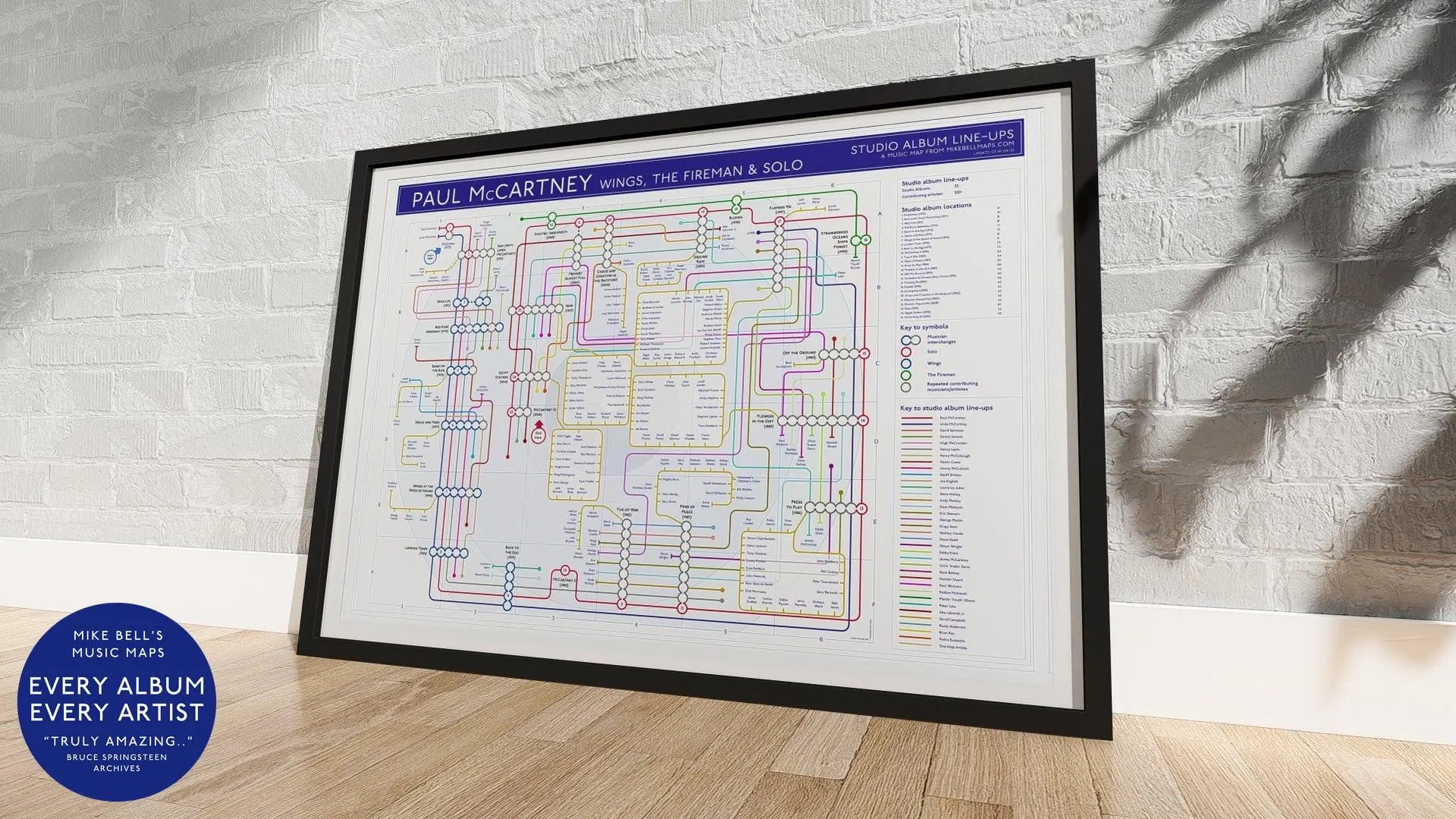

Other musicians were central to David Bowie’s sound, and my lineup research, which formed the basis of my Bowie art print, shows his catalogue as a web of recurring collaborators who helped him jump genres while still sounding unmistakably like Bowie.

Bowie as a Moving Bandleader on an Art Print

Across his studio albums, Bowie worked with more than 160 different credited players and singers, with only a small core returning again and again.

My art print makes this visible: beyond Bowie himself, the most frequent names are Carlos Alomar and Mike Garson (11 albums each), Tony Visconti (9), Sterling Campbell (7), and a cluster of others who appear across several distinct eras.

Thinking about Bowie as a bandleader rather than a solo auteur helps explain how he could change costumes so radically while his records still feel like chapters of one story.

Early years and the birth of Ziggy

On those first records, the guest list is short and almost tentative: Big Jim Sullivan’s guitar, Rick Wakeman’s piano, and Paul Buckmaster’s arrangements hint at the ambitious songwriter Bowie wanted to become.

The real leap comes with Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder, and Mick Woodmansey, whose work as the Spiders from Mars turned Bowie’s songs into towering glam-rock anthems and gave the Ziggy era its snarling guitars and muscular rhythm section.

Ronson’s arrangements and solos are so central that many fans argue Bowie might never have broken through as a rock icon without him.

Piano, producers and the art-rock turn

Mike Garson is the pianist who never quite leaves the story, first bringing avant-garde jazz and classical flourishes to Aladdin Sane and then reappearing on Diamond Dogs, Young Americans, and deep into the 90s and 2000s.

His harmonically adventurous style lets Bowie tilt songs toward cabaret, chaos, or tenderness at will, something your map shows by his presence on 11 different albums from early glam through Heathen and Reality.

Producer-bassist-arranger Tony Visconti is the long arc running from the late 60s to Blackstar, shaping everything from Hunky Dory’s chamber-pop feel to the dry, experimental sonics of the Berlin trilogy and the late-career records.

When Visconti is in the credits on your sheet, you can almost predict a bolder production approach, tape experiments, unusual mic techniques, and arrangements that push Bowie out of his comfort zone.

Soul, funk and the Alomar axis

Mid-70s Bowie doesn’t just change clothes; he changes groove, and Carlos Alomar is the pivot. My map shows Alomar as Bowie’s most frequent non-Bowie name, stretching from Young Americans through Station to Station, the Berlin period, Scary Monsters, and on into the 80s and early 90s.

As a guitarist, bandleader and co-writer, he anchors Bowie’s shift into funk and R&B, giving the so-called “plastic soul” era and beyond its clipped, rhythmic guitar language.

Alongside Alomar are drummer Dennis Davis and bassist George Murray, who appear together across key late-70s albums and form what fans often call Bowie’s rhythm section.

Their elastic pocket lets tracks stretch between American funk and European art-rock, making it possible for Bowie to put icy synthesisers and wild saxophone over grooves that still make sense on a dancefloor.

Berlin experiments and Eno’s atmospheres

The Berlin era is where my map shows a different pattern: fewer players, more emphasis on producers and sound designers. Brian Eno, appearing on multiple albums from Low onward, encourages Bowie to approach the studio as a laboratory, contributing synths, treatments, and a conceptual push toward ambient textures and non-traditional song forms.

Robert Fripp’s searing guitar on this period’s work brings another extreme colour, turning some tracks into almost psychedelic art-rock without ever entirely abandoning rock dynamics.

What stands out in my map is how the Berlin records actually rely on a relatively tight circle: Visconti, Eno, Alomar, Murray, Davis, with a few carefully chosen guests. The result is that the boldest stylistic pivot in Bowie’s career is executed not by starting from scratch, but by asking his existing collaborators to play in radically new ways.

Pop stardom and the Rodgers/Vaughan shock

Fast forward to Let’s Dance, and my map suddenly fills with new names: Nile Rodgers, Omar Hakim, Carmine Rojas, Lenny Pickett, Stan Harrison, Steve Elson, and a confident Stevie Ray Vaughan. Rodgers, known for Chic, rebuilds Bowie’s songs around lean, funky riffs and crisp arrangements, turning an originally folk-flavoured idea into slick, global pop.

Vaughan’s blues-infused lead guitar cuts through that polish, adding a raw edge that keeps the record from feeling like anonymous 80s pop.

Looking at my map, the Let’s Dance cluster is one of the clearest visual shocks: a dense new node of session players surrounded by only a few returning names such as Alomar. It underlines how Bowie often used an essentially new band when he wanted to make a statement that this era would sound nothing like the last.

Late reinventions and guitar adventurers

From the mid-80s through the 90s, the map becomes more fragmented, mirroring Bowie’s own exploratory, sometimes divisive records.

Reeves Gabrels, who appears across four albums including Outside and Earthling, is crucial here, bringing noise, alternative-rock and industrial guitar textures that pull Bowie into the same conversation as Nine Inch Nails and contemporary electronic rock.

Drummers like Sterling Campbell, who turns up seven times from Black Tie White Noise onwards, give continuity and power to a period otherwise defined by constant stylistic restarts.

Bowie’s late-90s and early-2000s work leans on increasingly sophisticated session players, Mark Plati, Gail Ann Dorsey, Tony Levin and others, who can handle both heavy rock and subtle, textural parts.

Often, Bowie returned to a small inner circle even when the album concepts seemed wildly different from one another.

Blackstar and the jazz vanguard

The cast list for Blackstar jumps out of my map as a self-contained mini-ensemble: Donny McCaslin on saxophone, Mark Guiliana on drums, Tim Lefebvre on bass, Ben Monder on guitar, with Jason Lindner and others on the broader orbit.

These are not rock veterans but cutting-edge jazz and experimental players, already known for integrating electronics, improvisation and modern rhythm concepts into their own records.

Bowie doesn’t ask them to play “rock with a jazz flavour”; he writes material that their language can inhabit, letting McCaslin’s sax and Guiliana’s hyper-detailed drumming reshape the feel of his final album.

Visconti returns as producer, connecting the very end of Bowie’s studio career back to the early 70s albums. That long arc, Visconti and a changing circle of musicians, means Blackstar sounds like both a radical departure and a summing-up, the final station on a line your map already traces from 1967 to 2016.

How my music map and the Bowie story fit together

What my map reveals are patterns that fans often feel but rarely see: who really formed the core artist, who appears just once, and which album sessions are crowded with new faces.

Art print owners can move album by album or era by era - the dense Ronson/Bolder/Woodmansey cluster of the Ziggy years, the tight Berlin group around Eno and Visconti, or the isolated Blackstar jazz unit.